Nonviolent and honest

Preliminary note: This text was originally written by me at the end of October 2018 for a Facebook group concerning polyamorous multiple relationships.

I compiled it as a personal response to the question of the “usefulness” of deploying “Nonviolent Communication (by Marshall B. Rosenberg)” [NVC] and “Radical Honesty (by Dr. Brad Blanton)” [RH] in the context of multiple relationships.

As I regularly refer to both forms of communication on my bLog (most recently in Entries 3, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 11 ) – which indicates that I attach considerable importance to these approaches in any case – I would like to introduce this article here as well since it bears similar impact concerning an oligoamorous context.

Brief description(s):

“Nonviolent Communication“

(NVC) was stipulated in written form for the first time in 1972 by the American psychologist Marshall B. Rosenberg.

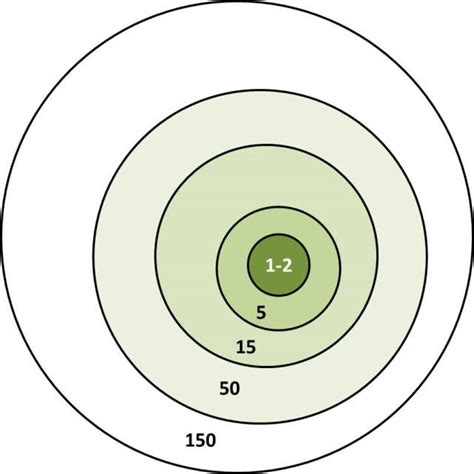

NVC is a concept of action which tries to enable people to interact with each other so that their flow of communication leads to more mutual trust and enjoyment of life. It is said that in this sense, NVC can be helpful in everyday communication as well as in peaceful conflict resolution in personal, professional or even political areas. Thereby the main focus is not on inducing other people to take certain actions but on developing an appreciative relationship that seeks to facilitate more co-operation and shared creativity while coexisting.

NVC focuses in particular on the various causes of conflicts; in the course of this it puts special attention on our somewhat “alienating”, sometimes downright violent everyday-conversations. The philosophy behind NVC encourages above all the exploration and the understanding of one’s own personal needs. It calls for training concerning one’s own perceptions, both in terms of what is actually happening in an interpersonal context as well as regarding one’s own emotions and feelings.

Even before Rosenberg’s death in 2015, NVC developed into various alignments and areas of application by the commitment of several of Rosenberg’s students (books, workshops etc.).

Since NVC has developed historically from the clinical psychology of Carl Rogers (a.o.), this kind of communication is occasionally criticised for being prone to manipulative usage, e.g. by exposing the conversational partner as “inadequate” or “inept”.

“Radical Honesty”

(RH) was stipulated in written form for the first time in 1990 by the American psychotherapist Dr. Brad Blanton.

RE is designed as a self-improvement program, which was developed by Dr. Blanton especially for conducting truly authentic conversation.

His philosophy asserts that lying and manipulation are the main sources of modern human stress, since – because out of shame or intentions of self-display – normally no real communication occurs anymore. Therefore, he calls for open and outright speech, even concerning painful or tabooed subjects. By this way, authentic conversance could be generated, which would make the dialogue partners more contented; an aspiration which cannot be gained by reservedness or concealment of one’s own bias.

Accordingly, Blanton’s “Radical Honesty” could also be translated as “Radical Openness” or “Radical Sincerity,” because that is the ultimate goal of the desired self-expression.

Dr. Blanton currently merchandises as right holder his communication-training by himself by means of various books written on the subject and especially in the form of self-directed workshops and internet-courses.

Since the philosophy of RH requires it explicitly to express a predominantly subjective “truth” in an extremely straightforward and almost blunt manner, RH is criticised – depending on the context – that it can be utilised to act deliberately unempathetic and advisedly offensive upon the interlocutors.

Both – the Nonviolent Communication (NVC) as well as Radical Honesty (RH) – are regularly recommended for intimate communication because of their conversational support, especially concerning challenging issues such as the convergence of quite different stances and starting points.

Particularly at this point, multiple relationships and ethical non-monogamy (such as Open Relations and Polyamory) come into play:

For example, on the websites Polyamory Weekly (esp. by Cunning Minx) and More Than Two (by Franklin Veaux) “Nonviolent Communication” is regularly highlighted as being advantageous for the conduct of talks and discussions in polyamorous relationships (I quote esp. these two websites, because seekers on the www will quickly come across one of these pages with a high probability).

Alas, if somebody would ask me in that context about my experiences – like e.g. “Oligotropos, do you think NVC and RH are useful for multiple relationships? ” – then my answer would be “No.” However, with the important addition: “I have learned that NVC and RH are mainly useful to me personally (my self-knowledge, the dealings with my inner self etc.).“

Why is my answer a “No” in such a way?

1) To my experience, with regard to NVC and in particular to RH, there exists the basic error that these forms of communication are primarily designed to “Let me tell you something…! “. And because I express an urgent irritation by means of a communication technique that is based on a nonviolent or radically honest context, I do not only obtain the right to finally express myself, but also – since I use one of the two most highly developed modes of communication on this planet – I’m thus gaining the right to finally be taken seriously, understood and heard.

I do not want to disappoint anyone of my readers who have been concerned with NVC or RH so far in their lives – but to my understanding this is not the idea behind the story, though frequently both kinds of communication are wielded for that reason in the first place. From my own experience, I also have great sympathy concerning this desire, because my wish to “to be finally understood / be heard” is at times just as urgent, of course.

In my opinion, what is at the core of NVC and RH instead?

As reluctant as I am to realise that sometimes myself: The attitude, to present myself (and my possible concern) to my communication partner(s) completely vulnerable and authentic: Completely maskless and unadorned – although with a quite steadfast (self)confidence. Thereby taking the risk in such a nonviolent and honest situation to entrust myself (and my intentions) unveiled to my interlocutors.

What purpose did the creators of NVC or RH want to strive for by that?

Concerning this point NVC and RH differ a bit from each other:

►NVC creates a moment in which my counterpart and I constitute the basis for a dialogue/process with the goal of mutual contribution to our respective well-being (commonly called: “win-win-situation”).

►In the case of the RH, a moment of extraordinary clarity emerges, since the dialogue partner(s) may react in an authentic way to the manipulation-free self-expression (or they may not!) – which leads to an unconcealed disclosure of the all-round motivations.

Now one might ask me “But isn’t that all the same – that authentic self-expression and the above-mentioned ‘Let me tell you something…!’? ” Again I refuse, since the brisk and by NVC or RH supposedly ennobled “Let me tell you something…!” applies only that part of both systems, which concerns the utterance of a subjective state/sensitivity (and the entitlement to be heard), but not the other – and in my experience much more important and difficult – part of empathic listening and the associated nonviolent or radical honest attitude.

2) Specifically, concerning multiple relationships, even more specific concerning any real existing human community, which is trying to handle a problem, an irritation, a circumstance, an obstacle by NVC or RH, I deny the immediate usefulness of these communication systems, especially if they are activated first of all in a crisis situation (the classic “kitchen-table-talk“). At first glance it might sound good if all participants agree to tackle a matter that has arisen in the upcoming talks by means of NVC or RH.

But: The complications regarding this kind of approach will prove that with such an application of NVC or RH these philosophies are used like “Office Yoga” only as a “technique” in order to achieve individual goals or situational desires of the interlocutors. However, neither NVC nor RH have been developed by their founders with the intention of providing a “technique” – a mere useful tool.

Both Marshall B. Rosenberg and Dr. Brad Blanton intended to formulate a basic attitude, an unique approach towards life – thereby resulting in a way of life. Both modes of communication focus on a highly authentic image of humanity, with a respective peaceful-benevolent or rather sincere attitude towards the world and its beings, with all the associated conditions (In comparison to the above citated “Office Yoga”, Yoga as a spiritual-holistic path would be the appropriate synonym here).

Now, if the aforementioned group sits down to solve their problems at the kitchen table and use NVC or RH without the associated attitude and only as “conversation technique” – on top concerning a problem which occurred outside the arranged conversation in normal-superficial and normal-reserved everyday life – the participants probably will have a rocky road ahead of them, which is unlikely to lead to mutual well-being or great authentic openness in the end, but rather to the experience that one couldn’t make oneself intelligible and that the others wouldn’t get across as well. And that NVC and RH are completely overrated because both would serve merely to spit uncomfortable subjective “truths” on the previously mentioned kitchen table, which, above all, increased discomfort on all sides.

In this way, the use of NVC and RH as mere conversational “techniques” also involves the danger of the “Wave under the carpet-szenario“: If the participants in a multiple relationship are not accustomed to address normal-human-related irritations self-reflected and promptly in everyday life, then – when the “kitchen-table-talk” takes place – a whole mountain of emotionally stressful concerns has already accumulated “under the carpet”, which is almost like a invisible killer-wave lurking below the table. If in such a moment during the “kitchen-table-talk” all participants struggle to communicate technically flawless “peaceful” or “open-minded”, the emotional overload is often already too high and the initiated conversation runs after a few sentences into danger to derail completely – thus going along with strife and tears – which, on top of it all, will be quite disenchanting concerning NVC or RH in respect of the self-proclaimed users.

PS: A merely “problem-oriented” application of NVC and RH could incidentally be an indication that these forms of communication are only used “technically” – but not integratively. After all, both approaches are just as excellent for expressing genuine joy and deep unanimity…

3) From what I have said under paragraph 2), I can deduce as well that NVC and RH are therefore not well suited to deal with common problems or behavioural patterns of the past (by this I mean a past in which the majority of the communication partners hadn’t deployed NVC or RH).

Since one didn’t act on the basis of NVC or RH at that time, the GOOD reasons for one’s own actions and talking and the reasons for the reactions of the others were based on entirely different origins. And I emphasise GOOD so much because I wish that all of us are superheroes in our own movie, who are trying their very best not to spread damage intentionally – but rather on the contrary are following their best motivations, abilities and intentions respectively (see Entry 11).

Accordingly, when our multiple relationship gathers around the kitchen table again today and tries to approach irritations of the past like “I know (exactly) what you did last summer…”, all participants run a risk of vain accusations and self-condemnation.

Example: That would be more or less the same as if one wanted to dissolve today, that one used to handle one’s dog by means of a prong collar (‘Man, I was nasty and violent at that time…‘) – and you, you subdued your dog even by using a riding crop (‘Man, you were much nastier than me and much more violent – and sooo thoughtless...’). But back then, everyone thought that he or she would act in a context of responsibility and general safety concerning the own pet, and they simply didn’t know better; even then all had plausible VERY GOOD reasons on their minds.

Accordingly, if NVC or RH are used during our kitchen-table-talk to attribute blame TODAY or to come up with accusations based on past behaviour, then the purpose of NVC or RH gets completely distorted.

NVC and RH may be used today to reflect, acknowledge or mourn in retrospect that we (all!) hadn’t a broader perspective back then – but this is exactly the reason why it is important not to use NVC or RH as a situational techniques but as integrated concepts into our own lifes:

That way I am beginning to understand that the most important part is to look at myself (and my deeds) in a peaceful-benevolent or open-authentic way. Only then can I reveal myself in front of the others and entrust myself to their goodwill and sincerity (And then it doesn’t matter anymore how they will react to my “self-disclosure”).

Besides: We should always be prepared to deal with “legacy issues” of our past and present. After all, there will always be somebody in our surroundings who does not share our set of communication system – and if it’s just your mother-in-law. Accordingly, it is good practise not only to excercise authentic speech, but also to listen wholeheartedly and as impartial as possible…

My conclusion:

…is of course a personal one. I myself have been working for about 8 years (as of 2019) with NVC and about 3 years with RH – and so far I have not been able to achieve a constant peaceful/benevolent or completely open-hearted conversation culture with my relationship people. But when I look at my abilities concerning interpersonal communication from 10 years ago, I can see a quite remarkable development compared to today – in my case thanks to NVC and the recognition of my needs.

Both NVC and RH are able to take us on an individual journey to discover and acknowledge our supreme needs and motivations.

Both philosophies are useful in dealing with our bias when entering a dialogue, they reveal how rarely we really trust our interlocutors, how shaky our self-confidence is and how seldom we muster the courage to show ourselves in our normal-inadequate humanity.

For the reasons mentioned above, however, I think that it is questionable to recommend NVC or RH to the participants of multiple relationships only/just/first in the case of emergency.

Few of us are able to distinguish our real needs from neediness or are able to distinguish inner sincerity from our superficial subjective “truth” – and still less are able to differentiate emotions from feelings. We all operate in “default mode” in a partly unpeaceful environment and are occasionally dominated by the understandable desire to display our motives in a more favourable light. Even if we enter our families or our (multiple) relationships we almost never cast off this skin automatically.

Last but not least: In respect of my own experience, concerning NVC as well as concerning RH the “careful listening” is disproportionately more difficult to master than the “careful speech”. Not unless we are able to “listen” (to the other dialogue partners) we will get a grasp how our trust, goodwill and sincerity is actually evolved – and whether we are ready to accept the others lovingly in their undisguised normal-inadequate humanity. Whether and how our (self)honesty and empathy skills really develop, we will experience right there.

Creating that special quality for yourself seems to me the real challenge of good communication.

That’s why Marshall B. Rosenberg presumably suggested lesser talk but more content when it came down to communication in relationships. Or, as his eastern counterpart Thich Nhat Hanh puts it: “Sometimes it’s enough just to sit and breathe together…¹”

¹ The buddhistic monk Thich Nhat Hanh is sometimes considered as the “Eastern Master” of Non-violent Communication. He has put forth his thoughts in the books “The Art of Communicating” (2014) and “How to love” (Mindful Essentials 2014).

Thanks to Adi Goldstein on Unsplash for the photo.