How many are a few?

Today I received a message from the mainland, in which I was asked how many the much-cited “few” would be, who were supposed to congregate in one of those oligoamorous relationship-networks. And who in any case would be allowed to establish that number, especially if somebody would be falling in love again – because that probably could lead to the commencement of another relationship.

I think that these two questions are extremely exciting. And – like the questioner – I also think that the answers are somehow connected. I believe as well that these questions concern many oligoamorous core topics – therefore, instead of a short answer, I am going to reply to it by means of a whole bLog-entry, by which I will try to approach the entire subject area.

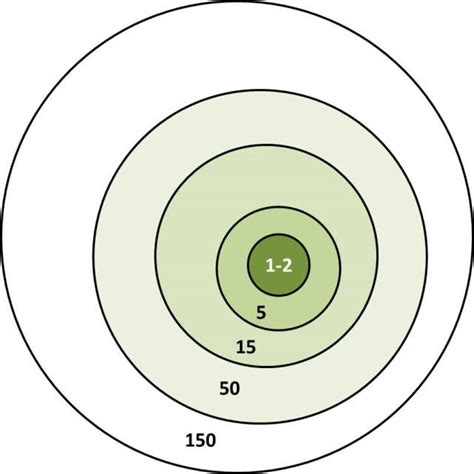

In the 1990s, the British psychologist Robin Dunbar discovered an interesting correlation regarding the magnitude of communities of primates in relation to brain size and the number of possible individuals of such communities, from which he eventually derived the so-called “Dunbar’s number“, which he determined to be about 150 applied to human beings. For better understanding, he partitioned this quantity of 150 people by several concentric circles, with the individual at the centre of the innermost circle – representing you or me.

The first and smallest circle was designated by Dunbar with the specification “intimacy and nearness” and he assigned to it the amount of 5 persons. He pointed out that in this “circle” those people were gathered, with whom someone would usually be living together, who would know each other very well, with whom there would be a very high degree of social interaction and to whom the highest degree of trust among each other would be available.

He designated the second circle with the term “friendship” and allotted its quantity to 15 persons. To that circle he assigned all those close-knit relations to which there would still be quite strong ties, e.g. dreams, plans, joy and sorrow would be shared, even though perhaps there would no longer necessarily be residential or financial companionship and most of the time wouldn’t be spent together anymore.

The third circle can be called “participation” with about 35-50 people in it, who are approximating what many of us call “acquaintances.” Accordingly it contains e.g. our more companionable colleagues, steady attendants from our local parish or convivial club members with whom we are dealing on a regular basis – but in any case a group whose affiliation with us is already becoming quite heterogeneous (of inconsistent composition). Additionally Dunbar himself also pointed out that this group included all so called “friendships” that are not maintained regularly (anymore).

The fourth circle, which would consist of 100 to 200 people – depending on the individual, finally may be called “exchange”. It contains all those persons who we would know just by name, and with whom we only would have isolated dealings and transactions such as a doctor, a home cleaner, possibly own customers, etc.

[Some Dunbar-models even work with larger circles of about 500 to 1500 people. These depict areas in which we may still recognise the face of a person and deduct that this is someone who probably works in our company or in our educational establishment, although their name wouldn’t be realy available to us – or people about which we are pretty sure that they live in our hometown or in our neighbourhood, but we do not have any biographical data about them at all (and never cared to acquire it)]

Of course we are – to quote Patrick McGoohan¹ – not just numbers but real people. Nevertheless, Dunbar’s number and its “circles” surprisingly were found and still can be found in many human correlations in real life, which appear to emerge without any artificial arrangement, for they actually seem to do justice to certain “human criteria”, to which we (in)voluntary react amazingly favourable as well as aligned. Anthropological observations have shown, for example, that African self-supporting villages are still frequently divided into two settlements when the mark of 150 to 200 inhabitants is exceeded. Camps of cooperating hunter-gatherers from the early period of humanity to present-day Amazonia regularly consist of no more than 35 to 50 individuals to ensure the efficiency of a foray.

And from the 12 disciples of Jesus to workshops, immersion courses or team building seminars offered on the internet you will encounter regularly required attendance figures of 8 to 15 participants maximum.

Particularly with the latter we enter the oligoamorous relevant range.

For it is interestingly enough that many spiritual and psychological examples in particular point to an intimate “upper limit” of approximately a “dozen” participants: Be it the disciples quoted above, training groups in Catholic seminaries, the size of church-related home groups, witches circles (in neo-paganism) or conversation circles and therapy groups, as well as small ensembles of musicians who do not need a conductor (and therefore “intuitively communicate”).

For the intensive involvement with a common topic or with each other, there were always quite tangible reasons concerning such an approach: Because somewhere around that “dozen” lurks certainly a threshold of discomfort – and beyond it a “group” becomes a “crowd” wherein either individuals are short-changed or the whole bunch splits up into cliques and factions (thereby establishing exactly that kind of “heterogeneity” by which friends become mere “acquaintances” in Dunbar’s 3rd circle…).

On the other hand, less “tangible”, but all the more important seems to be that beneath that threshold we humans appear to be more likely to engage in a “group process”, wherein we dare to open ourselves up – even to the possibility of conflict and the risk of vulnerability (as well as to the display of fallibility and weakness!). Concerning the size of the group or rather of the relationship, this size seems to facilitate the possibility of tolerating different opinions and needs. And even if anger or harm is experienced, a feeling of clearness an predictability seems to be sustained that in the end respect and trust can be reestablished.

So if you ask me as the author of this bLog-project describing committed-sustainable multiple relationships, I say: According to my experience, an amount of up to 12 participants ensures that all parties in an oligoamorous relationship are still able to display commitment and sustainability as well as they are able to experience it. Because, first of all, the very heterogeneity of a group beyond that point will affect any individual’s commitment, because integrity and reliability can quickly become literally a supra-human Herculean task due to the increasing input of multifarious stimulations. And, secondly, the criteria of sustainability like dependability (consistency), appropriateness (efficiency), and satisfaction (sufficiency) are increasingly watering down [these aspired “values” of Oligoamory are to be found in Entry 3].

Is there an “ideal size” for me as an author as well?

The Jewish proverb says, “He who saves a single soul saves an entire world.” (Jerusalem Talmud, Sanhedrin, 23 a-b [similar statement incidentally in Qur’an 5:32]). If I consider this metaphor in connection with the Anaïs Nin quote “that each new person represents a world in us, a world not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.” (Entry 6) then it is very likely that initiating a single relationship with “just” one other person could reveal an intense journey of discovery into a completely unique universe that will occupy us with its infinite diversity for a lifetime.

And to be honest: The mere prospect of such a journey of discovery is already perfectly able to engulf us completely when falling in love with a new person.

Exactly this phenomenon often is such a profound issue, especially when opening an existing relationship to a multiple relationship: For (usually) one of the participants a “new world” opens up, which initially often leads to formidable turbulences in terms of resource management, time distribution and a reorientation concerning personal needs and their satisfaction.

However, the challenges of resource management, time distribution and needs remain an important subject in multiple relationships, even if the initial, and often hormonal abundant, upheaval begins to ease.

Accordingly, more sensitive natures (as I am as Highly Sensitive Person / SPS, for example) may soon be totally involved with “only” two close relationship-persons – which, by the way, certainly occasionally sparks the desire for triadic triple-constellations (though perhaps as shortsighted as well as understandable: human beings are prone to putting themselves in the place of the “central point” of their relationship network…).

However, consistently reviewed – and concerning Oligoamory – we probably will find ourselves somewhere in Dunbar’s “First Circle”: A group of up to 6 people (5 + myself, of course) who share a high level of intimacy and nearness as described above, which is so important in respect to the maintenance of mutual trust as well as mutual familiarity.

►To keep in mind: we are talking about the intensity, the nearness and the mutual relatedness in our loving relationships. Accordingly we are referring to those people with whom we make decisive contribution to our lives, essentially create our lives – and whom in return we allow to exert a rather decisive influence concerning our lives. Because (hopefully) we are thereby able to establish loving ties and faithful relationships, in which we may experience the imbuing certainty that all participants are reciprocal that important to each other that they involve the others even in considerations regarding individual decisions and personal conduct – in thought at least.

This last paragraph conveys a very oligoamorous core idea, because, to my mind, the predictable “amount” of the “few” is directly related to the ensuring of oligoamorous values (especially regarding commitment, entitlement, honesty, identification and sustainability [see Entry 4 for reference]).

This is exactly where the transition to the second question “And who decides? ” comes in.

Basically – just for the record – there always will be fascination, attraction, “feelings for one another”, infatuation and falling in love.

There is also a strong probability that quite often this will affect the “smallest possible unit” – involving two people for a start (whether they are already in relationship or not). As a result, the participants of this “smallest unit” then engage in a possible process of getting to know each other – and potentially also of learning to love each other.

When this process finally passes into the consideration concerning an emerging relationship, even involuntarily, questions regarding respective life plans are affected in any case, like for example: How do the participants see themselves? As solitary entities, who relate themselves situationally and selectively – or rather as member of a social group and potentially a bigger picture?

An oligoamorous view on relationships contains very much the curiosity to experience oneself as “more than the sum of ones parts” – and thus also to deal intensively with the own human nature as “fellow being”.

However, such a request already contains a certain degree of desire for self-awareness and hence for self-responsibility as well: “I want to contribute and share in a common treasure of knowledge, gifts and experiences. I’ll be revealing a lot about myself (as Dunbar argued for the first and second of his “circles”), and the other people involved will open up to me – which is impotant, because without this reciprocity, it is hard to establish any trust.”

So in the end, it is exactly this “self-responsibility” by which everyone finally has to decide for her/himself to what extent new people will fit into the personal relationship-network in the medium and the long run.

Because in respect to my associates, which I choose in a distinctive way (and my relatives choose me), I would finally like to participate in the potential of our community, which in turn is composed of the potential of all the individuals in it – with their peculiarities and aptitudes. Accordingly, in the best case, I benefit from both. And this is precisely the reason why those factors of nearness and togetherness are so vital to Oligoamory.

To some readers this last part may sound quite ideal and maybe even a bit aloof.

Therefore, a “cross-check” with the personal attitude towards the people in our own relationship-network can sometimes be a thought-provoking impulse.

For example, I have noticed for myself, that I have difficulties with the conduct of long-distance- or weekend-relationships and they pose a constant challenge to me because I often find it hard to appreciate a degree of reciprocity that satisfies me. To all intents and purposes, I usually share such relationships with people who should have a great significance for my life – but we are often separated in terms of space or time. In my case, this often leads to a feeling that both the relationship and the people involved therein do not quite take a proper shape or literally “become real” – just because they participate to a lesser degree in my everyday life. Personally, I have learned for myself that I have experienced these relationships as oligoamorous difficult to sustain – even medium-term, because I seem to be more fascinated by an “exciting feature” there than to really perceive myself in a genuine relation to a person of flesh and blood.

Which takes my journey back to Robin Dunbar, who would probably point out to me that in those cases my relationships are in the considerable danger of deviating from my first and second “circle” to the rim of the third – and loved ones and friends could become mere “acquaintances” that way.

For I myself do not want to hope that my fascination as an optional add-on feature will last as long as possible – because we all deserve it to be truly accepted and be loved as real people with our unique nooks and crannies by our chosen loved ones.

And in this regard, I would like to invite with my conception of Oligoamory to favour quality and intensity over quantity and diversion in any case ².

¹ Did you know? The quote stems not originally from lyrics by Iron Maiden but from the television series “The Prisoner” from 1967.

² In contrast to the ambitious perceptions I put into my version of Oligoamory, I deem it perfectly possible that – I’d say – less sophisticated multiple relationships are covered and can be conducted by the terms of Polyamory. The critical thoughts in this regard, which have therefore led to my own approach, I have laid down in Entry 2.

Thanks to Christine for her inspiring questions and to rawpixel on unsplash.com for the fine picture!